DogBitesMan » Journalism » When journalists fall from grace – sometimes they’re victims too

When journalists fall from grace – sometimes they’re victims too

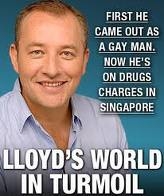

The jailing of an Australian foreign correspondent in Singapore for drug taking highlights yet again that dangers for journalists come in many forms.

Worst of all are the hundreds of deaths every year of journalists working in their own or other people’s countries. These continue to be tolled out regularly on professional websites such as the Committee to Protect Journalists at http://www.cpj.org/, together with the thousands of media workers seriously injured every year while doing their jobs.

These are the most obvious victims of our trade.

Less obvious – but occasionally more public – are cases such as Peter Lloyd’s.

Until his contract was terminated this week because of his imprisonment, he was the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Asian correspondent based in New Delhi, covering one of the busiest, most fascinating but also most turbulent regions on earth.

During six years working out of Bangkok and New Delhi, Lloyd covered a number of disasters and smaller human tragedies, including the Asian tsunami, suicide bombings in Pakistan, the 2002 Bali bombings and the sex trafficking of children.

In between, of course he also covered a host of positive, less distressing events, but it was the death and disaster which did the damage to Lloyd’s psyche.

In interviews after being charged with drug trafficking and drug taking, Lloyd told of suffering increasing intermittent confusion, nightmares, daytime flashbacks and periods of memory loss.

His former wife, herself a journalist, said she saw her husband change over the years of covering some of the worst terrorist and natural disasters in decades.

Lloyd himself said he had “done more mass casualties stuff than your average soldier does”.

But unlike soldiers or emergency workers, all Lloyd and his media colleagues could do at scenes of horrific suffering was watch, record and report.

This feeling of powerlessness is repeated time after time by journalists witnessing death and destruction the rest of us see only on the pages of newspapers or the screens of our TVs. There is often, of course, a temptation for journalists to drop their cameras, recorders or notebooks and take part in rescue and life-saving efforts, but they are seldom properly equipped and so must stick to the job they know well, reporting the suffering for the rest of society, so we can understand better what is happening in the world.

The fact that Lloyd resorted to drugs to help him through post traumatic stress has been seen by many commentators as just another manifestation of the coping mechanisms most journalists use to deal with their own nightmares. Many have friends and partners to whom they can vent their frustration and hurt. Some play sport or take long runs to burn the pent up energy and quell the visions. Many foreign correspondents, traditionally separated from friends and families and isolated in hotels have traditionally resorted to alcohol. But in most countries, alcohol is legal, whereas drugs such as methamphetamine – which Lloyd pleaded guilty to taking – are not.

An underlying question, asked particularly by older, more hardened journalists, is whether modern practitioners have become “soft”.

The fact that the ABC did not seem to offer its journalists sufficient counselling is, to these old hacks, laughable.

“We saw far worse from more often,” they say. “We never needed counselling. We went back to the hotel, got drunk and then woke up the next morning and did it all again.”

And maybe they did. Maybe they were tougher, maybe they were special people not easily affected by the horrific things they witnessed. One hopes, for their sake, that is so.

But modern journalism demands different qualities and is practised in different ways.

We increasingly expect journalists to be highly educated, multiskilled, sensitive and thoughtful, not a creature separated from society but a real person who is part of it.

Globalisation too has produced a situation in which the victims of death and disaster are more and more like the journalists who are reporting on them.

Once upon a time, journalists could enter communities – whether at home or overseas – and see people quite different to them, perhaps not quite as human. Nowadays, we are all part of an increasingly global family, so that the people journalists report on are increasingly like us.

Little wonder therefore that sensitive, thoughtful journalists suffer with them.

Nothing can condone the breaking of drug laws in countries such as Singapore, and Lloyd himself has admitted the offence, for which he has been jailed for 10 months.

But given that Lloyd was originally charged with the much more serious trafficking offence, and given that the fact that the courts wanted to send a clear message about drug taking through such a high profile case, one hopes the judge recognised to some degree that Lloyd was essentially a good man suffering for the rest of us.

First published in The News Manual in December 2008

__________

You can read more on some of the practical aspects of covering death and disaster in these chapters in The News Manual:

Chapter 39: Introduction to investigative reporting

Chapter 40: Investigative reporting in practice

Chapter 41: Investigative reporting, writing techniques

Chapter 42: Death & disaster, introduction

Chapter 43: Reporting death & disaster

Filed under: Journalism